By Steve Boehler with special guest Les Binet

I first heard of Les Binet when looking for good articles and books on marketing and marketing science to read. It had been many years since my P&G days and I missed the rigor of the P&G approach. I was eager to find some disciplined, thoughtful marketing science to read.

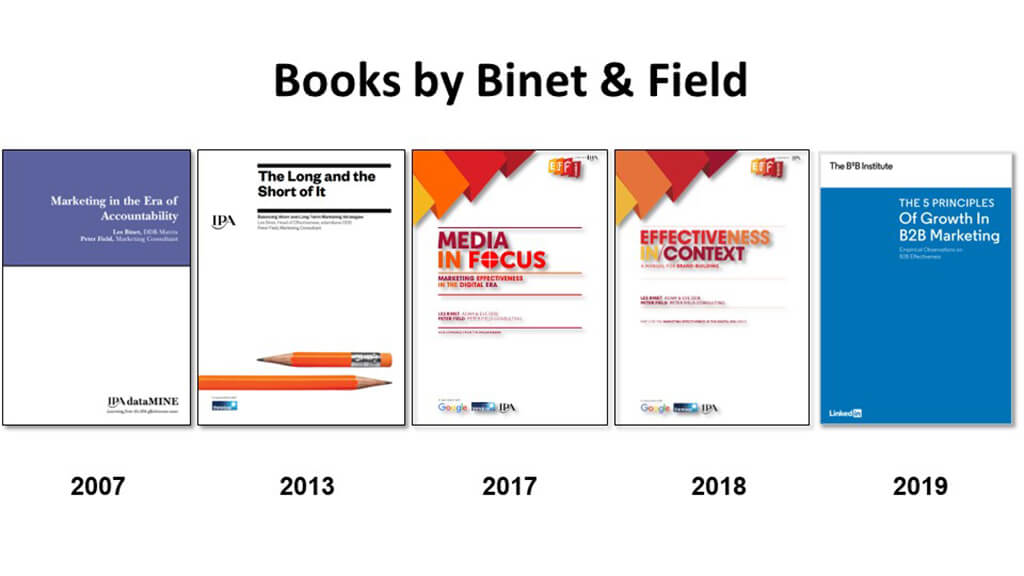

I came across The long and short of it by Les Binet and Peter Field and was hooked.

Since that day I have become an avid follower of Mr. Binet’s thought leadership. Les has many strong opinions and I was lucky enough to corner him for the following conversation covering a wide number of topics ranging from his concerns with attribution to his work in Share of Search. If you’re a marketer or an agency exec, this discussion is for you!

Recently there has been a great deal of attention paid to brand and performance marketing and the differences between the approaches. You’ve talked a lot about the fact that there can be a merging of brand and performance. And in fact, that great brand work is actually driving a lot of performance. And it’s driving long term performance. In a typical funnel model is there a place for that thinking? Is there a place in the marketing mix where the brand part just breaks and the solution has to be pure performance? I’m thinking about things like paid search which seems performance specific.

Les: I think everything is on this sort of continuum, pure brand to pure performance. Most things do a bit of both, but with a different mix. To some extent it depends on the audience’s frame of mind. Imagine for example you’ve got an entertaining ad for car insurance and at the end there’s a URL or a phone number. Even with the call-to-action, so much of this is pure brand as most people are not going to be in the market right then for car insurance. If you just randomly see the ad at one time of the year, you are on average going to be about six months away from renewal. So most people are gonna see that ad and it’s just gonna be brand to them.

But, a small fraction of the audience may be in the market to renew their car insurance online as the ad comes on air. And for that tiny proportion of the audience, they process it in a different way and they’ll think “that’s the brand I should go with.” So for a small portion of the audience even the most “brand” ad will be a piece of performance marketing.

Even something like paid search can drive brand. I’m sure that there are brands that I’ve seen regularly in my search results. I’ve never clicked on them, but, because I’ve seen those brands come up a lot, I’ve got a vague awareness of them now. So I think even paid search can have a slight brand effect.

I am sort of smitten by Share of Search. Part of the reason for that is that we work with clients of all shapes and sizes. We work with the folks that have half a billion $ to spend on advertising and folks that have a million US dollars to spend. Most of those folks at the smaller end don’t have armies of data scientists and can’t afford complex econometric modeling support. That makes the Share of Search thing so appealing. Despite all this, I rarely see a company in the US using Share of Search as a proxy for demand or market share. Is that because it’s still years away from mass adoption?

Les: Let me start by going back in time. Long before Share of Search, around 1993, I worked with Share of Voice. Somebody came up to me in the agency and said we need a way of thinking about how to set the advertising budget for one of our clients. Could we maybe do something looking at share voice versus market share? The planner in question had obviously read John Phillip Jones. I thought to myself, oh, you idiot, that’s not gonna work. You know, that’s far too simplistic. But of course it did work! And it worked very well.

So, fast forward to 2011, and another guy in the agency says to me, we need something like a digital share of voice. Could it be share of buzz? And I thought, are you an idiot? That’s not gonna work. I went away and looked at it and share of buzz didn’t work. But then I looked at share of search, and I thought, ah, wow, this actually works extremely well! So really from about 2012, I was developing that idea, but I’m very lazy and slow, and often don’t get around to writing and publishing things for a long time. So I really didn’t publicize it very much until a couple of years ago.

James Hankins had also been working on this and publishing about it. So eventually with us both publishing and speaking on the topic it has caught on in some circles.

But why hasn’t it taken off even more? I don’t know. I am seeing a drip drip of people using it. I think there are one or two little subtleties about Share of Search that are necessary in order to use it well. For example, if you just look at the raw data, it’s very noisy. I think some people may look at that and think it doesn’t work. These charts don’t look like Les’ charts. And that’s because I do lots of smoothing and I look at long-term trends. People who are interested in share of search very often are only interested in the short term. I think there’s a bit of a misunderstanding of about what it’s for and what it’s about. See, the obvious way of thinking about this is search is the customer journey. It’s people on their way to the website to buy. There’s a long history of thinking about it that way and that’s a very short-term thing. You know, it’s like, you search and then you buy eight minutes later or something like that.

When they start to look at Share of Search with that very short-term lens, Share of Search doesn’t particularly reveal very much. Where share of search reveals interesting patterns is if you look over long time scales. I think this is slightly counterintuitive cause everyone thinks of search as being a short-term direct thing. What I’m saying is it’s also an indication of very long-term shifts in society and effectively in our awareness and mental availability of brands. Not at the individual level, but at the group level in society. Some people who come from a digital background just don’t seem to have that way of thinking.

Often people say to me, well, I’ve looked at the data and I couldn’t see anything. My advice is to expand out, look at longer time frames and smooth the data. Then start looking at the search patterns and then you can see something. I also think that some people just don’t believe it will work for them. For example, people that work in FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), don’t think consumers search for chocolate or shampoo or soup stock cubes, so it’s not part of the customer journey. But the thing is, I don’t necessarily believe that it’s only about people being on the customer journey. It’s about whether or not the brand is in people’s heads at all. You could search for the Hershey’s brand, and that’s not because you are on your way to a website to buy a bar of chocolate. It could be because for some reason Hershey’s has come into your mind, like, when did they change the color of the packet? Or are there new flavors or pack sizes? Maybe how the nutritional value compares to Nestle. Either way, you don’t search for a brand unless it has some mental availability.

See Les Binet’s IPA presentation here.

What advice would you give to a marketer that wanted to start dabbling in Share of Search or needed to convince the rest of their organization that this was a good idea?

Les: I would say look at long-term trends, smooth the data, and be patient. I was working with a retailer and an hour before the meeting, I wondered what’s happening to their search patterns. And I was able to put together a 15-year global search trend versus their major competition, and then use that as a jumping off point for a discussion about how their brand was doing. They said “well, we thought that, but we’d never came up with any data to confirm our hypothesis.”

It was quick and easy and free. But you do have to be a bit intelligent with the data and creative with the data and interrogate it in multiple ways. It’s not just a thing where you press a button and the answer comes out. I think this is another thing related to what you said about agencies having proprietary tools. Everybody wants tools that will just spit the answer out, but what is really valuable? Often the tools that you need are quite simple, but what you need is clever people who can think and frame hypotheses and interrogate data and so forth. And maybe some of the people that work in this world are a bit spoon fed, you know.

Recently there’s been some back and forth across the internet and on LinkedIn about attribution versus econometric modeling. And I know you’ve been caught up in this…

Les: There’s certainly a prominent discussion going on. And I think the discussion is a good thing. It will go on for a while because I believe the performance folks are stuck on attribution more than they are on econometric modeling.

You noted that you sometimes dive into your research after “getting a buzz in your head”. What’s that next thing that we’re all going to be talking about because you caused the discussion to happen?

Les: I have to confess, I do have a little list of things I’m going to write about, and some little truth and data bombs that I’m gonna drop out there. But I can’t tell you about them yet. You’ll just have to wait!

I’ve got plenty more that I want say about attribution. We haven’t finished that particular debate. And I do think it’s an a really important one. It’s not a new debate, really. I mean it kind of goes back a hundred years, because what we think of as digital attribution is just a modern version of direct response analysis which Claude Hopkins was using in 1923. And it’s always been wrong.

Claude Hopkins would look at coupons cut out of newspapers and he’d think, we got a thousand responses, a thousand US housewives writing in to buy this new electric iron or whatever it was. And so this ad generated a thousand sales. Well, no, it didn’t. They may well have bought that iron when they next went to Chicago on the train or something. This is quite a nice analogy: the ad is like the door into the store. If a department store tried to measure the effectiveness of a door by counting how many people walk through it they might think we’ve got a thousand people that walked in through that door and bought products so that door generated a thousand sales. No, it didn’t. That’s just how they came in. And they might also look at their display windows and think, well, nobody came in through the windows.

So those window displays, they’re not selling anything. So let’s replace all the display windows with extra doors and that’s bound to make our sales grow. So that thinking has been wrong for a hundred years. I can remember our chief executive, talking about this in roughly 1990 saying, this sort of direct mail attribution thing is basically fraud. And I don’t how they’ve got away with it for so long, and they’re still getting away with it today. It’s digital today. But there are so many people who are invested in this. I mean, half the MarTech industry is based on this with billions of dollars at stake. But I think it’s crumbling now, partly because of problems with data privacy and cookies and all that stuff, which means that a lot of the data’s beginning to evaporate.

And I think at the same time, digital marketing is growing up, maturing, becoming deeper, more experienced. So when I talk to people at Facebook and at Google, I’ve always been quite surprised. I had a conversation with someone at Facebook not long ago saying thank God we’re finally getting these nerds to move away from crappy attribution models. So it feels like the timing’s right.

What other things? I’m thinking a bit about the changing shape of the media marketplace. That’s what I was doing just before we started this call. I’m seeing some interesting signs in the data that the growth of commercial online media may be plateauing. I’m still interrogating the figures, but it’s interesting. In the UK we have this data source called Touchpoints, which is very robust survey mobile-based panel and they poll people every 30 minutes to find out what media they’re using. And according to that survey, it looks like total consumption of online commercial media peaked about five years ago and has been flat or even fallen back slightly since then, which is not the rhetoric you hear.

You know, we all assume that digital media just keeps growing, but it looks like it might have stabilized. I think part of what might be going on is that there’s still growth in subscription services like Spotify and Netflix. But the bits that carry advertising look like it’s stabilized.

If that’s true, and if the UK’s representative of a relatively mature digital market, that kind of means that the marketing market for online advertising eyeballs and ears has stopped growing. I don’t think that the marketplace is ready for that yet. I think that will be a shock. I mean, it’s a bit like the shock when Netflix’s subscription growth suddenly started to slow. And lots of investment is based on the idea of that online advertising is just gonna keep on growing… but maybe it stops.

Les, as I sit here in the largest advertising market in the world, I find it fascinating that the great thought leaders writing about marketing effectiveness seem to be from somewhere else. Why is that?

Les: I think that might be true today. If you go back a hundred years, though, the cutting-edge thinking was in the US. Back in 1923 Claude Hopkins and people like that were the absolute cutting edge of advertising measurement theory. I think Claude Hopkins’ book, Scientific Advertising, came out in 1923, so it’s a hundred years old this year. And I think US thought leadership probably would’ve been true right into the 1960s.

Then in the 1970s and 1980s, British advertising researchers began to kind of pull forward a bit. One thing that’s been very influential in the UK is the IPA, the body that represents advertising in the UK. The IPA really encouraged very rigorous measurement of advertising effectiveness.

Along with this push came an award scheme, The IPA Effectiveness Awards, intended to make the study as rigorous as possible. There was an industry push to find any way of really measuring the effects of advertising in hard business terms and the effectiveness awards were part of that. The first IPA effectiveness awards competition was in 1980. I don’t know if the Effies in the US were kind of like copying the IPA Effectiveness Awards or vice versa. But the IPA awards were always much more rigorous and demanding. And so that really pushed British advertisers to think a lot about the hard effects of advertising and measuring it in hard business terms. And fairly early on in that work, British advertisers started embracing econometric modeling or market mix modeling. I think it was first applied to advertising in the US in the 1960s, but we really seemed to embrace it quite fully from about 1980 onwards. Australia is another market which had an effectiveness award scheme based on the IPA Awards, so that they had the same kind of momentum there.

And obviously the other people to think about are the Ehrenberg Bass crew. Andrew Ehrenberg was in the UK and Frank Bass was doing the same in Australia. And then when they merged as the Ehrenberg Bass Institute, that gave a powerful impetus to Australian marketing. So there’s a couple of these little sort of nucleation sites that helped. Peter Field, and I got involved in all this through the IPA Effectiveness Awards. Byron Sharpe obviously comes from that Ehrenberg Bass tradition.

Many smart researchers were colliding outside the US like Ehrenberg Bass, the IPA, Tim Ambler, Byron Sharpe, Peter Field, me and others. I suppose the bigger question is why didn’t that happen in the US? I think there may be some obstacles in the US with anti-competitive behavior laws and overall less collaboration.

This effectiveness discussion brought me back to the early days of my career. I spent the first 10 years of my career at P&G in brand work. In the early eighties, the company had created awards to lionize great advertising. And they had a really simple but profound (at the time) definition of what “advertising that works” was: 12 consecutive months of market share growth. If your brand’s market share grows for 12 consecutive months, you have advertising that works. It worked for P&G because deep in the company’s soul and culture was a belief system that great advertising was critical to growth. They believed in advertising as much as anybody! But we certainly didn’t believe in collaboration with our competitors on “what works”.

Les: Well, if you found out what worked, you wouldn’t tell anyone else, would you?

In the UK there’s a lot of very polite collaboration sometimes. It’s quite funny because I play that collaboration role at the IPA but I also work for an agency and we are quite competitive. There are times when I have to say to other agencies: “look, I’m sorry I can’t come and help teach you about this stuff because my role is to drive you out of business.” You know?

As a marketing consultant that does a lot of agency search, I love the fact that you collaborate because when we hear agencies proclaim that they have some proprietary tool or technology, my eyes immediately glaze over because everybody’s got tools, everybody has science. At least I wish everyone had tools and everyone had science, but the ones that do have them pretty much have the same tools as each other.

Les: I’m not a great believer in tools. It’s quite funny. People often come to me say “so what are the tools that you use to do this stuff?” And I say “Excel, PowerPoint, a pen.”

The other thing about the US is that in the last 20 something years there has been so much excitement about technology. You know, it’s all very focused on tech rather than the underlying thing, which I think is basically people really.

Another thing that happened was that the British invented account planning, which I think of as leaning on the other end of the spectrum from effectiveness measurement; it’s not “was it effective” as much as “how do we create something that will be effective?”

Les: Yes, planning was a British invention, and I think it’s fair to say we probably still lead the world in planning.

Do you know why account planners are called account planners? The originators, Stanley Pollitt and Stephen King, disagreed about what they wanted to call it, but they agreed that it was a hybrid job between a media planner and an account manager. Stephen King wanted to call it a “Planager”, but they settled on “Account Planner”. So, right there, you’ve got that combination of business strategy at the top end and at the bottom end media optimization. And the bit that kind of goes in the middle is understanding how you get from a business goal to a marketing goal, to a communications proposition, and how you influence people and what people are like, and what do you need to say to someone to get them to do the thing that will deliver the revenue. A good account planner should understand business strategy, marketing strategy, media strategy and should have a really good understanding of people. And we always said that a great account planner should be both a left brain and a right brain person. “A physicist who plays the violin”, as we used to say.

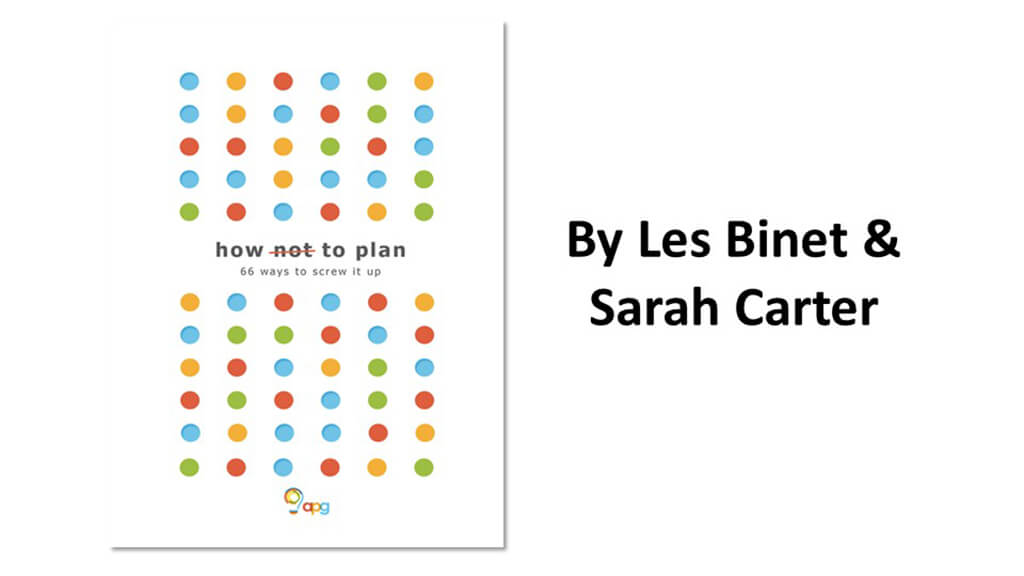

People who’ve got very wide interests and can think both mathematically and psychologically, if you like. And with high empathy. Probably the best planner I’ve ever worked with is my friend Sarah Carter, who I wrote How Not to Plan with. She’s brilliant like that. She’s incredibly sensitive to people and has great empathy and great understanding of social trends in a way that I’m humbled by. But she’s actually quite mathematical as well. She can go and do qualitative discussions and read anthropology, and she can correct my spreadsheets. I think we are getting fewer people like that. I’ve definitely seen that the planners are much less mathematical now than they used to be. And they don’t get out in the field and meet consumers much now. So rather than doing focus groups in people’s homes in the north of England, they do desk research on Google.

Of all the stuff that you’ve published, what should people immediately read?

Les: Well, that’s going to depend on who they are for a start. For general marketers, I guess probably The long and the short of it, cause it’s the best overall introduction to the research Peter Field and I have done and our ideas. Then they should read, Effectiveness in Context, which makes the point that you need to tweak the rules depending on what situation you’re in. I think that’s particularly important with notions like the 60:40 rule. In Effectiveness in Context, we said the balance for some brands may be different than for other brands.

And then if you are a planner, read How Not to Plan. That book is much more fun and lighthearted.

I personally think How Not to Plan is such a fun book along with being so informative. And there’s something there for everybody: a story or a principle or a different way of looking at things for everybody depending upon their situation. It’s quite magical.

Les: It took a long time to write because Sarah Carter and I started it as a monthly column. It took six years of writing these monthly columns. Then we had to edit and re-edit it to get it into book shape. Sarah’s very good at, you know, cutting out my boring stuff. It ended up being about nine years work! I think that paid off because people do seem to like it.

Is there anything that somebody else wrote that you are really jealous about?

Les: Yes. I always say that if anybody should read one book about marketing, it’s How Brands Grow by Byron Sharp. And read that before you read anything by Binet and Field or anything like that. It’s a much more important book. How Brands Grow is rooted in the marvelous research of Andrew Ehrenberg and his various followers in the UK and Australia. It is the most important thing for anyone to know about marketing. If you don’t understand that stuff, you’re not gonna get anything else.

Another one was a paper Paul Feldwick and Robert Heath wrote for the Market Research Society called 60 Years of Using the Wrong Advertising Model. This one is all about emotions and how advertising wasn’t really persuasion or communication, it was all about associations and feelings and all that stuff.

Les Binet is a world-renowned expert in marketing effectiveness and evaluation. He has written extensively on how advertising works, how to make it work better, and how to evaluate it. In particular, his work with Peter Field has attracted international attention. As the CMO of Unilever put it, “Les and Peter have made a huge contribution to our understanding of how marketing drives growth and profit for brands. Marketers everywhere should pay close attention.” In his “day job” he serves as Group head of Effectiveness at adam&eveDDB.

Steve Boehler, founder, and partner at Mercer Island Group has led consulting teams on behalf of clients as diverse as Ulta Beauty, Microsoft, UScellular, Nintendo, Kaiser Permanente, Holland America Line, Stop & Shop, Qualcomm, Brooks Running, and numerous others. He founded MIG after serving as a division president in a Fortune 100 when he was only 32. Earlier in his career, Steve cut his teeth with a decade in Brand Management at Procter & Gamble, leading brands like Tide, Pringles, and Jif.